Island of the Sirra.

January 18, 2023

“Take us to your ruler,” said the second legate to the first person they met upon coming ashore. The dirty and emaciated young woman, wearing only a ragged loincloth, her hair hacked short, stared torpidly at him then turned and pointed. The two legates and their party passed by her, and when she saw that none desired her services she sank down on the stone quay to resume staring with vacant eyes out to sea. Between her shoulders a huge Sirra hung, its suckers penetrating her flesh, its slime flowing down her spine to crust the rear of her loincloth.

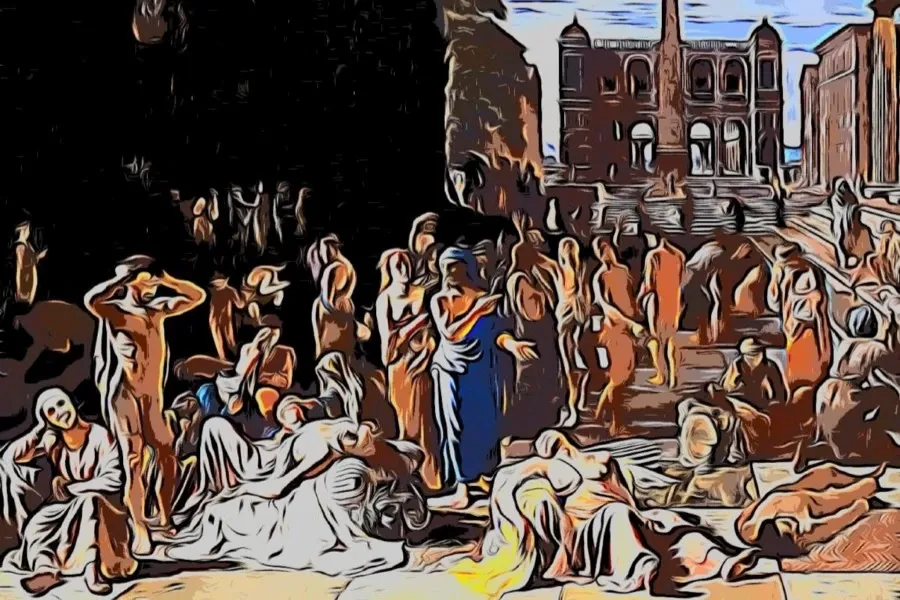

The legates made their way up the broad avenue toward the prominent building she had pointed out. Everywhere were stricken people, ridden by the Sirra. They lay in the gutters, near death, sometimes in death. They wandered about, glassy eyed and muttering. They ran about, wailing and flailing and cursing the Sirra. They stood in small groups and raved fiercely but feebly at each other and as the legates came within hearing they were amazed to find that these people were not truly quarrelling, but that each was complaining that the others were not listening. Sirra, with their suckers folded inward and curled into bright blue, scale-armoured, slimey-glistening balls, lay on the ground everywhere. When the first legate kicked one, it rolled across the avenue and came to rest, still curled tightly.

With a fanfare, a procession emerged from the palace of the island’s ruler and came down the avenue toward the legation. The legates halted and let the ruler approach them. As they stood waiting, people shuffled up to gape or to ask them, ”Have you come to help us fight the Sirra?” or “Can you help us, please? The Sirra are killing us. Tell us what to do.” The legates stood solemnly in their white robes, holding their rods of office in the crook of their arms.

The ruler’s face was grey against his purple robe and gold diadem. “Hail. I am Seephor, king of the isle of D’nai. What brings so splendid a legation to my domain in its hour of ultimate disaster?”

The legates bowed. The first legate stepped forward. “Hail, mighty Seephor. We bring the greetings of the senate of Atlantis to the wise and glorious king of D’nai and, if the gods will it, a remedy for the great calamity which has befallen his heretofore prosperous kingdom. For, several of his stricken subjects have escaped from D’nai and by good fortune reached the shores of our great and blessed land of Atlantis. This one has returned to his native land and benevolent king to show that, through the skill of the famed physicians of Atlantis, both can be forever rid of the Sirra.” The first legate gestured behind him, to the D’nai who blanched at the angry glare of his king but stepped forward, turned, and stripped to the waist to show the healed scars on his back. At this sight, the gathering crowd of D’nai began to hiss. The two legates glanced sideways at each other, then at the captain of their armed escort, then at the healed D’nai, then they nodded to the physician and turned their attention back to the glowering king. The legation’s escort began to tense.

The physician stepped forward and drew a bronze lancet from his satchel. “Oh, great king Seephor,” he said, ”Allow me to demonstrate how simple is the procedure by which you and your subjects may be free of this loathsome affliction. Who would be my first patient?” The D’nai cowered back as he advanced toward them with his lancet held high.

“Enough,” shrilled the king. ”Everyone knows that to remove the Sirra is to kill its host.”

“With respect, I fear that the great king is mistaken,” said the first legate, ”I ask his indulgence while our learned physician explains the procedure to him.” But the crowd retreated, and many began to wail, as the physician tried to approach them.

The physician had another idea. He picked up a Sirra from the street and began to stroke it. The creature unrolled itself, spread its red-tipped suckers, and began to ooze saliva. “To safely remove the Sirra one merely inserts the lancet through this gap below the third row of scales, into its brain.” This he did, as his D’nai audience gasped, and several fainted. “With the parasite dead and the spines of its suckers relaxed, one merely pulls it free from the host’s body. This is painful but is over quickly and there is no permanent injury. With a special salve which I have perfected, healing is complete within weeks. The craving for the addictive agent in the parasite’s saliva dissipates within days.” The physician flung the limp Sirra to the ground and drew a cloth from his satchel to clean his hands and his lancet. The crowd stared in dull awe as the dead creature’s mantle faded from bright blue to mottled shades of grey and its yellow underbelly turned brown.

Seephor’s face was now flushed and sweaty. He trembled, and found his voice with difficulty. “No, you do not understand. We cannot live without the Sirra.”

“O wise and mighty king,” said the first legate, ”We thrive without this Sirra on our backs. Your subject who has had his Sirra removed is now as vigorous as we.” The two legates glanced again at the expatriate D’nai. His face wore a sad satisfaction that the Atlantans were seeing for themselves what they had been skeptical of when he and his companions had told them, but also a dreadful anxiety about the outcome. “You and your subjects who bear the Sirra are ill and dying, your fields and cattle untended, your impressive city falling into disrepair,” concluded the first legate.

“You do not understand the problem.” Seephor wheezed, and paused to regain his breath and his composure. “We must live in harmony with the Sirra. It is the way ordained by the God of the Sirra. But the Sirra are not following the way. You must help us to fight the Sirra. We must force them to realise that they are acting wrongly.”

“Great king,” said the first legate, “ with respect, you have asked us to help you to fight the Sirra, and you have asked us to help you to convince them that they are wrong. Which is it?”

“You must help us,” said Seephor. “You are strong, we are weakened from fighting the Sirra. We have been fighting them with all our strength for so long but they will not see that they are wrong. We are becoming so wearied…”

“Great king, one either fights one’s enemy, or one tries to reason with him. One cannot do both at the same time. I do not see that you are resisting these creatures in any way. Neither can I see that they have any more intelligence than an ordinary kind of leech, therefore how does one reason with them?”

The king suddenly lunged forward, shrieking; “You blasphemous Imog. You insult the God of the Sirra.” The legates leaped back. The captain of their guard had sensed the snap coming and, quick as a cat, was between them and Seephor, his buckler under the incensed king’s chin, his sword at the half-draw. His men were as quick to form a ring between the legation and the groaning, milling crowd. Seephor staggered back, lost his balance, and fell. His attendants were too surprised and too torpid to help him. He sat on the ground, flustered and unable or unwilling to rise. His own guard knew better than to challenge the fit Atlantans.

The second legate helped the king to his feet, apologised grandly for the incident, absorbed all blame for it, and strenuously assured him that the legation had come only to help in any way that it could and that it meant no disrespect to the D’nai’s gods or to the dignity of their king. Seephor cut him short and pushed himself away. “Leave our island, you barbarians.”

The first legate spoke. “We are unable to leave yet, King Seephor. I assure you that we mean no harm to your realm and rule, but you and your people are ill. You are not in your right minds. You must not dispute with, and threaten, those who try to help you by showing you how you may be rid of the Sirra.”

“You do not help us by speaking like an Imog, by affronting the God of the Sirra like an Imog, by returning this Imog here, who has spurned the god of his parents, his king, and his country, the god whose gift of the Sirra has in the past been such a blessing to all three, and comes now to brazen his contempt for …, for…, the Sirra that were such a blessing to us in the past… this Imog.” The ever-growing crowd rumbled its approval, and the returned D’nai looked apprehensively at the hateful glares surrounding the bronze ring of soldiers and back at the legates.

“Great King,“ shouted the first legate over the crowd, ”Our own gods do not command us to do things which first make us foolish and then slowly kill us. Men are right to find other gods when those which they have worshipped in the past now clearly seek to destroy them.”

The second legate shouted; “O wise king, when and why did the Sirra cease to follow the divine way?”

Seephor pleaded, ”We have no choice but to accept the Sirra. We cannot remove them.”

“Why not, Seephor?” shouted back the first legate.

“We will die. We must live in harmony with the Sirra.”

“We show you proof that you will not die.”

“But no one can reach behind to remove his Sirra.”

“By all the gods in heaven, help each other, you people!”

“But the pain of removing the Sirra cannot be endured. Our hearts will stop.”

“This D’nai and others have endured the pain. For those who chew the lotus leaf, to overcome their addiction is agonising, but it must be done if they are to live, rather than chew the lotus.”

“But we cannot remove the Sirra.”

“We will remove them for you, if we must.”

“That would bring the wrath of the God of the Sirra down upon us.”

“Is not his wrath already upon you?” asked the second legate. “What could he strike you with that is worse than what you are suffering now. I do not see what you have done to deserve it.”

“We do not deserve it. But we must live with the Sirra; it is the way, the only way. The Sirra were not like this before. Something is wrong with them. We must fight to make them understand that they are taking too much from us, and we are dying.”

“We know that the Sirra were less malignant in former times, but they were never beneficial. You must rid yourselves of them forever.”

“No, we will die if we remove the Sirra.”

The second legate had meanwhile whispered an order to the captain of their escort, who whispered to two of his soldiers while the second legate leaned into the physician’s ear. The two soldiers easily snatched a young man through their cordon and pinned him face down. A young woman tried to hurl herself through the cordon, shrieking ”Not my husband. No, no.” The soldiers flung her back into the crowd. The physician bestrode his patient, who whined and screamed as the Sirra was pulled out of him, but did not resist the two soldiers.

The crowd raged: ”You cannot do this.” “You have no right.” “Leave him alone.” “Barbarians.” “Imog.” Some spat and threw pieces of rotten food which the armoured Atlantic soldiers endured as the legates sheltered behind them.

Some D’nai began to pull up the pavements. The Atlantean captain roared out, ”Throw those cobbles and we will respond with arrows!” They stopped.

The soldiers raised the patient up. He dropped when they let him go. They pulled him up again. One shinned him. “You aren’t injured! You can stand!” He stood.

The physician held up to the crowd his second dead Sirra of the day. “O, you people of D’nai,” he shouted, “Why would you be enslaved by this vile creature when you can be free of it so easily.” He flung it into the crowd, then turned to his patient and ordered the soldiers to unhand him. “This man is now free. In a few months he will be as well and strong as we Atlantans.”

The returned D’nai spoke to the patient, but loud enough to be heard by the crowd. “It’s true. Give it a little time. Life really is much better without the Sirra.”

The patient bolted back into the crowd, where several people proffered opened and oozing Sirra. He moaned as a new Sirra worked its way into his flesh, while his wife clung to him and the crowd whinnied in overwrought empathy, before he sank down in languor.

“To the temple,” shouted Seephor. “We must shun these blasphemers, these barbarians, as we shunned the Imog of old. We must sacrifice twice to the God of the Sirra: once to bring the Sirra back to their right way, and again to be rid of these new Imog who have come to give us further grief in our time of travail.” He turned and walked toward the temple and the crowd followed him, and the legation were soon left with the Sirra and those D’nai who were no longer able to walk. Keeping a good distance, they followed the king and his subjects to the temple.

“I believe that there is only one course of action left to us,” said the first legate.

“But these people are in a state of dementia,” said the second legate. “What you propose would bring the reprobation of the gods upon Atlantis.”

“No,” said the physician, “They have their reason. They have not their will.”

“There are ten thousand people on this island.” said the first legate. ”Must we transport that many soldiers merely to watch over the stupid and spineless, to prevent them from harming themselves? The senate will never approve the expense!”

“If we let them be, perhaps this affliction will run its course like a plague that leaves some immunized survivors to repopulate their island.”

“If this affliction is like a plague, then it is prudent to eliminate the source of infestation or it may spread to other lands, even our own.”

The legates could not agree until a tumult began from within the temple and gangs of men ran out and began picking up the people who lay helpless in the streets, who feebly fought and pleaded, starkly terrified of the fate that awaited them as they were dragged into the temple. Cords of firewood began to be hauled toward the temple as the chant rose from within: ”Sacrifice, sacrifice, sacrifice…” The legates glanced at each other then nodded to the captain, who quietly issued the orders to his soldiers, who drew their swords and began their bloody work.

Later, the returned D’nai wandered among the temple’s pillars and the bloody corpses and the bright blue balls, his greatest hope for his own land and people shattered, his worst fear realised. He looked up at the statues of the deified founders, all portrayed with tiny Sirra clinging to their bare shoulders. He slumped down and wept.

The hundred Atlantic soldiers needed four days to finish the D’nai. They met no resistance, not even serious attempts to flee or hide from them. They grew sick of listening to confused attempts to convince them that they had no right and were not following the correct way. Many D’nai chose to uphold the royal decree to shun the Atlantans and ignored their executioners until the last instant. The Sirra merely separated from their dead hosts, rolled up, and waited. The Atlantans put down all domesticated animals that were too far gone from neglect and released the rest to the wild, and two soldiers who were caught looting were scourged at the stake. Finally, they raised a pillar on the most prominent spot on the harbour front, onto which they chiselled an account of what they had done, warning whoever might happen to land there about the danger of the Sirra.

The returned D’nai stood at the stern of the white galley of Atlantis as it was rowed toward the harbour mouth. The first legate asked him, ”Who were these ‘ Imog’ your countrymen spoke of?”

The D’nai answered without looking at the Atlantans. “The elders told of a time when some people rebelled against the law and refused to bear the Sirra. They were shunned: forced to go and live like wild animals in the uplands and they all died eventually.”

The second legate asked, “Where did the Sirra come from and when did the D’nai first begin to bear them?”

“I do not know. I know only what was read in the sacred texts.”

“When did the Sirra begin to go wrong?”

The D’nai thought long before answering. “The end began soon after the succession of Seephor, five years ago, though most of my people blamed the old king. I believe that the bad Sirra were present long before that, together with the …with the less malignant Sirra.”

“Did the D’nai ever practise human sacrifice before the prevalence of the bad Sirra?”

“No.”

“Coxswain,” shouted the first legate, “Let us be away from this infamous land whose people chose slow death over freedom. Whip the slaves until they make the oars crack.”

Comments ()